by Julie Havlak, Carolina Journal News Service

RALEIGH — Republican U.S. Sen. Thom Tillis went on the attack Monday night.

He had to.

Tillis went after Democrat Cal Cunningham more like an underdog challenger than an incumbent senator and former speaker of the House in North Carolina. Tillis finds himself in one of the nation’s most contested Senate races, the outcome of which could decide whether Democrats take control of that house of Congress.

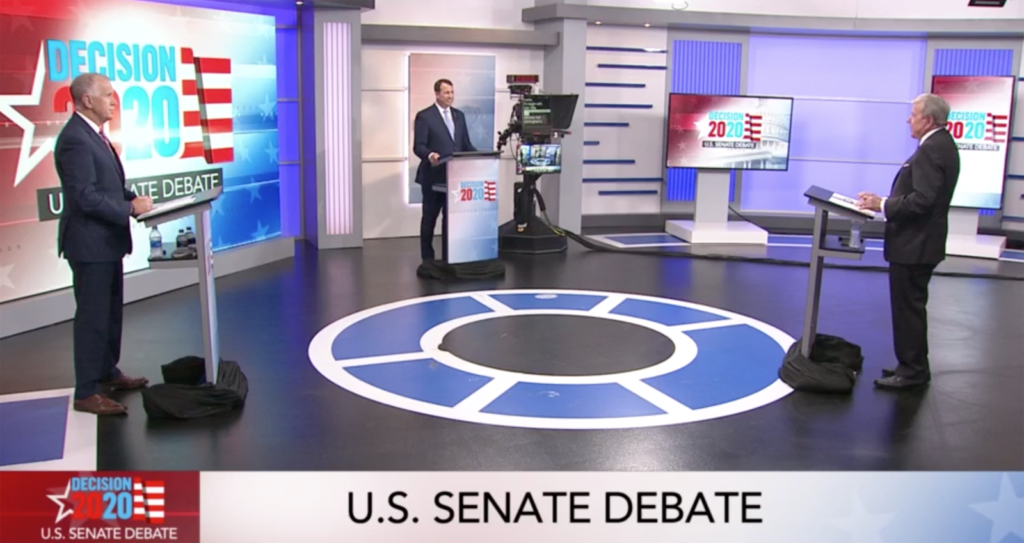

Tillis will probably get the down-ballot votes of Trump supporters. But undecided voters are key. He had the chance to persuade them in a debate with Cunningham on Sept. 14.

When Cunningham gave him an opening, Tillis latched on. He didn’t let go.

Cunningham said he would hesitate to take any vaccine approved before the election.

“Yes, I would be hesitant. I’m going to ask a lot of questions, I think that’s incumbent on all of us right now, in this environment,” Cunningham said. “We’ve seen an extraordinary corruption in Washington, political and economic corruption, that has deluded and distorted decision making.”

Cunningham didn’t explicitly blame Trump, distorting his own position into an “anti-vaccination statement,” said “Mac” McCorkle, professor in the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University.

Tillis pounced.

“We just heard a candidate for the U.S. Senate look into the camera and tell 10 million North Carolinians that he would be hesitant to take a vaccine. I think that’s irresponsible,” Tillis said. “In a crisis, you don’t undermine an effective process in the FDA, you don’t shorten the line of people who desperately need a vaccine. That statement puts lives at risk.”

Cunningham will need to get sharper in the next two debates, says McCorkle. The Democratic challenger can’t rest on an anti-Trump vote.

Both candidates are battling to introduce themselves before their rivals can define them. That seems odd, considering Tillis’ long political career.

An unusual predicament, says Andy Taylor, political science professor at N.C. State University. The most recent Civitas Institute poll showed Tillis trailing, 38%-41%, with 16% undecided.

“Tillis was just focused on trying to take Cunningham out in a way you don’t usually see from an incumbent senator — unless it’s an incumbent in trouble,” said McCorkle.

The president has become a “tricky” issue for Tillis, who trails Trump in the polls in North Carolina. The senator must improve his lukewarm standing among Trump supporters, while also attracting undecided voters, said David McLennan, professor of political science at Meredith College.

“There are a lot of Republicans who are unsure of Tillis,” Taylor said. “He’s been a critic of [President Donald] Trump, a friend of Trump. It’ll be interesting to see how he moves. It’s hard to do Trump by half-measures.”

The senator has waffled in his support for the president. But Tillis has voted with the president’s agenda more than 90% of the time, and he defended Trump’s management of the pandemic during the debate. He gained Trump’s endorsement in June.

Tillis tried to squash Cunningham’s appeal to unaffiliated, ideologically moderate voters. On COVID-19 relief, for example, Senate Democrats used a procedural move last week to block a $500 billion GOP-sponsored bill even though it passed 52-47. Cunningham said he would have opposed the measure because it didn’t spend enough. The response seemed to surprise moderator David Crabtree, who asked Cunningham if a bill likely to become law taking a “first step” wouldn’t get his support. Cunningham said it wouldn’t.

On law and order, Cunningham tried to distance himself from the movement to defund the police. But Tillis didn’t let go. He decried the shootings of police officers, suggesting Cunningham would be anti-police and friendly to riots.

“There is systemic racism in this culture,” Tillis said. Then he cited legislation he championed as House speaker which gave restitution to surviving victims of the state’s eugenics program — a program Democrats let stay in place when Cunningham was in the Senate.