Senate sends ‘sweeping’ criminal justice reform bill to governor

By Jeff Moore, Carolina Journal

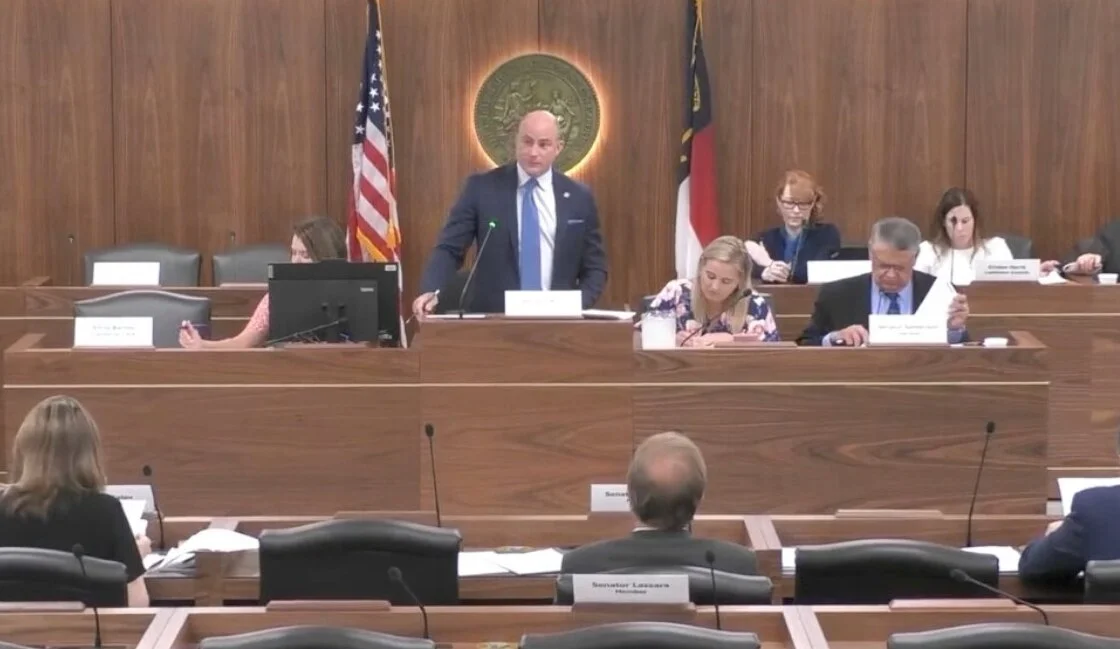

Criminal justice reform is a bipartisan issue, a phrase lawmakers frequently use when noting the parties coming together and advancing legislation. True to form, Senate Bill 300, Criminal Justice Reform, was approved by the General Assembly with strong bipartisan support and awaits the governor’s signature.

"Since coming to Raleigh I’ve worked tirelessly to correct the decades of overcriminalization implemented by previous legislatures,” bill sponsor and former prosecutor Sen. Danny Britt, R-Robeson, said in a news release. “This bill squarely takes aim at that and implements reforms that benefit both our law enforcement community and the public they’re sworn to protect. I hope Gov. Cooper sees the value in this bill and immediately signs it into law.”

This bill doesn't exist in a vacuum, as Republican-led legislatures have in recent years advanced several criminal justice reform bills, including Raise the Age, the Second Chance Act, and the First Step Act. The latter, Republican lawmakers have noted, overturned mandatory minimum prison sentences imposed by then-Sen. Roy Cooper and Democrat-led legislatures.

Further changes within S.B. 300 include provisions to:

Create a public database of law enforcement officer certification suspensions and revocations.

Require all law enforcement officer fingerprints to be entered in state and federal databases.

Authorize law enforcement agencies to participate in the FBI’s criminal background check systems.

Create a database for law enforcement agencies of "critical incident information" which includes death or serious bodily injury.

Require that written notification of Giglio material (credibility issues that would make an officer open to impeachment by the defense in a criminal trial) be reported.

Allow health care providers to transport the respondent in an involuntary commitment.

Provide in-person instruction by mental health professionals and develop policies to encourage officers to utilize available mental health resources.

Require the creation of a best-practices recruitment guide to encourage diversity.

Expand mandatory in-service training for officers to include mental health topics, community policing, minority sensitivity, use of force, and the duty to intervene and report.

Increase penalties for those who resist or obstruct an arrest and while doing so injure a law enforcement officer.

The legislation contains provisions to decriminalize local ordinances and institute a working group to recodify state statutes to streamline the criminal code.

Regarding the former, the bill says a person may not be found responsible or guilty of a local ordinance violation if either there are no new alleged violations of the local ordinance within 30 days from the date of the initial alleged violation, or the person provides proof of a good-faith effort to seek assistance to address any underlying factors related to the violation, such as homelessness or mental illness.

The latter provision would establish a nine-member bipartisan working board “to make recommendations to the General Assembly regarding a streamlined, comprehensive, orderly, and principled criminal code which includes all common law, statutory, regulatory, and ordinance crimes.”

During testimony before the General Statutes Commission in April 2020, Jon Guze, senior fellow for legal studies at the John Locke Foundation, argued on behalf of establishing such a recodification group for the purposes of cleaning up what he described as “a sprawling, incoherent, and inaccessible body of criminal law.”

Addressing the problems with such a haphazard criminal code, Guze wrote:

“The sheer number of criminal laws and criminalized regulations (and the haphazard and careless way they are documented) make it impossible for ordinary citizens to learn about and understand all the rules that govern their everyday activities and subject them to criminal liability. Moreover, because so many of those laws and regulations criminalize conduct that is not inherently evil and does not cause harm to any identifiable victim, citizens cannot rely on their intuitive notions of right and wrong to alert them to the fact that they may be committing a crime. And yet for many crimes, including most regulatory crimes, no mens rea (mental state) element is specified in the definition. As a result, a citizen can be found guilty without proving any criminal knowledge or criminal intent at all.”

Guze pointed to a 2017 report compiled by Jessica Smith, a leading criminal law expert and professor at the University of North Carolina School of Government. In it, Smith argues the problem of incoherent criminal law sprawl could be solved through a systematic process of recodification.

Her suggestion was well-received in the General Assembly then, but it ultimately failed to advance. In a 2018 interview, Smith told Carolina Journal, “There’s no central database for collecting criminal ordinances. It’s impossible to say how many things we’ve made criminal in North Carolina.”

That can be a monumental problem. People should be able to get notice to inform their behavior accordingly, Smith said, adding that even a misdemeanor — especially one committed without the knowledge of the law — can ruin someone’s life.

The labyrinth that's North Carolina’s complex criminal code is also expensive and serves to create confusion in areas that should be clear. As such, the provisions creating a recodification working group and decriminalizing local ordinances represent a significant and positive undertaking included in the bill, in addition to the myriad expansions of training and accountability requirements for law enforcement officers.

Cooper has 10 days to sign, veto, or allow the bill to become law without his signature.